Wieland Schmied

The Individuality and Significance of Hundertwasser’s Painting

Hundertwasser not only began as a painter, his painting was also the point of departure for all the other activities he has undertaken. His painting influenced his pictorial theories and his “grammar of seeing”. It is the foundation of his architectural manifestos and his commitment to an organic architecture worthy of man, in which the individual decoration of the façade and the right to paint the frame and wall around the windows oneself play a role. Finally, all his print graphics are based on his painting, whose images it varies with other means – silkscreen painting or lithography.

Hundertwasser made his first appearance as a painter about 1950. His pictures were a personal attempt to find an answer of his own to the situation of art at that time. At that time the avant-garde – in Vienna, too – was widely defined by tachism, whose basic tendencies Hundertwasser perceived to be pure psychological automatism, as practised, for example, by Arnulf Rainer, who was his age, in an extenuation of surrealistic (and other) demands. Hundertwasser could not entirely evade the impulses and suggestiveness of the avant-garde, as little as its results satisfied him. So he tried to find a way of his own. He wanted to answer automatism with a transautomatism, the slow, “vegetative” growth of a picture out of cells and lines, to counter art informel with a plethora of new forms, formulae and coded references.

In doing so he took on the naive world view of a child and the primitives, on the one hand, such as that he found in the pictures of Henri Rousseau and Paul Klee, among others; on the other hand he went back to the formal elements of Art Nouveau and Secessionism, which had particularly fascinated him in the works of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. And so it happened that one critic (Gottfried Sello) characterised Hundertwasser’s beginnings – in a play on words based on the German term for Art Nouveau, Jugendstil (Youth Style) – as a combination of “child and youth styles”. Both sources of his art have the superficiality of the image layout and the relinquishing of the customary perspective in common; in addition, the Secession style featured the structuring of the two-dimensional forms, the luxurious, sumptuous colour and the curvilinearity, the verve of the sensitive line suggestive of movement and life.

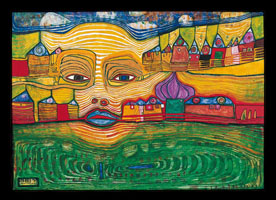

From the beginning Hundertwasser assimilated all elements of his painting he had taken from tradition and integrated them into his own poetic cosmos. This poetic – or psychological – dimension of the picture is what is most important to him: it is the chance to find the world in his picture inhabitable, to be able to live in his own painting. That is why not only the individual forms in Hundertwasser’s pictures are “animate” – even when the coded references evade being identified objectively – and why it is above all the spiral which has since 1953 become the dominant formal motif in his painting and something of its trademark: formed by an irregularly and often exuberatingly growing line whose movement can be read in two directions, inward and outward, which takes on and incorporates the world while yet only winding about itself, protecting itself.

A major part of the effect of Hundertwasser’s painting is colour. Hundertwasser uses colours instinctively, without associating them with a definite symbolism of even his own invention. He prefers intensive, radiant colours and loves to place complementary colours next to one another to emphasize the double movement of the spiral, for instance. He also likes to use gold and silver, which he pastes onto the picture in a thin foil.

Two large groups of motifs determine the content of Hundertwasser’s painting: one comprises a world of forms representing analogies to vegetative growth and an animistic nature; the other is the repetitive use of architectural code symbols: houses, windows, gables, fences, gates. It is one of the idiosyncrasies of Hundertwasser’s art that both motif groups are inextricably linked: vegetative forms seem static, to solidify to architecture in order to last, whereas everything constructed seems to have grown organically, to have been produced by nature herself. The houses often appear to be located in mountains or on hills; fences can sprout out of the ground like grass; the onion tower is a striking illustration of the intimate link between both realms.

His painting technique is also his very personal affair. Hundertwasser likes best to use paints he has pulverised or prepared himself, which he applies without mixing. Similarly, he prepares the priming ground himself; for prime coating, paint mixture and varnish he has developed various recipes of his own, all of which are designed to guarantee a long life for his pictures. In many of his pictures he uses oil, tempera and watercolour techniques in one picture to achieve a contrasting effect between the matte and radiant parts of the picture.

Hundertwasser’s painting has gained acceptance in many places – pictures of his hang in major public and private collections of Europe, America and Japan – but it has had no lasting influence on the artists of his generation or that succeeding it. Hundertwasser has remained the outsider he always was. He will probably go down in art history as one of those individualists who have always existed outside the main current in all epochs, who can only be fitted into the image of an age contrapuntally and from a distance. Today the position of his painting is singular and unparalleled. That defines its incomparable stature, but also the narrow confines of its effectiveness.

Excerpt from: Wieland Schmied, Hundertwasser and his Painting, in: Hundertwasser KunstHausWien, Cologne, 1999